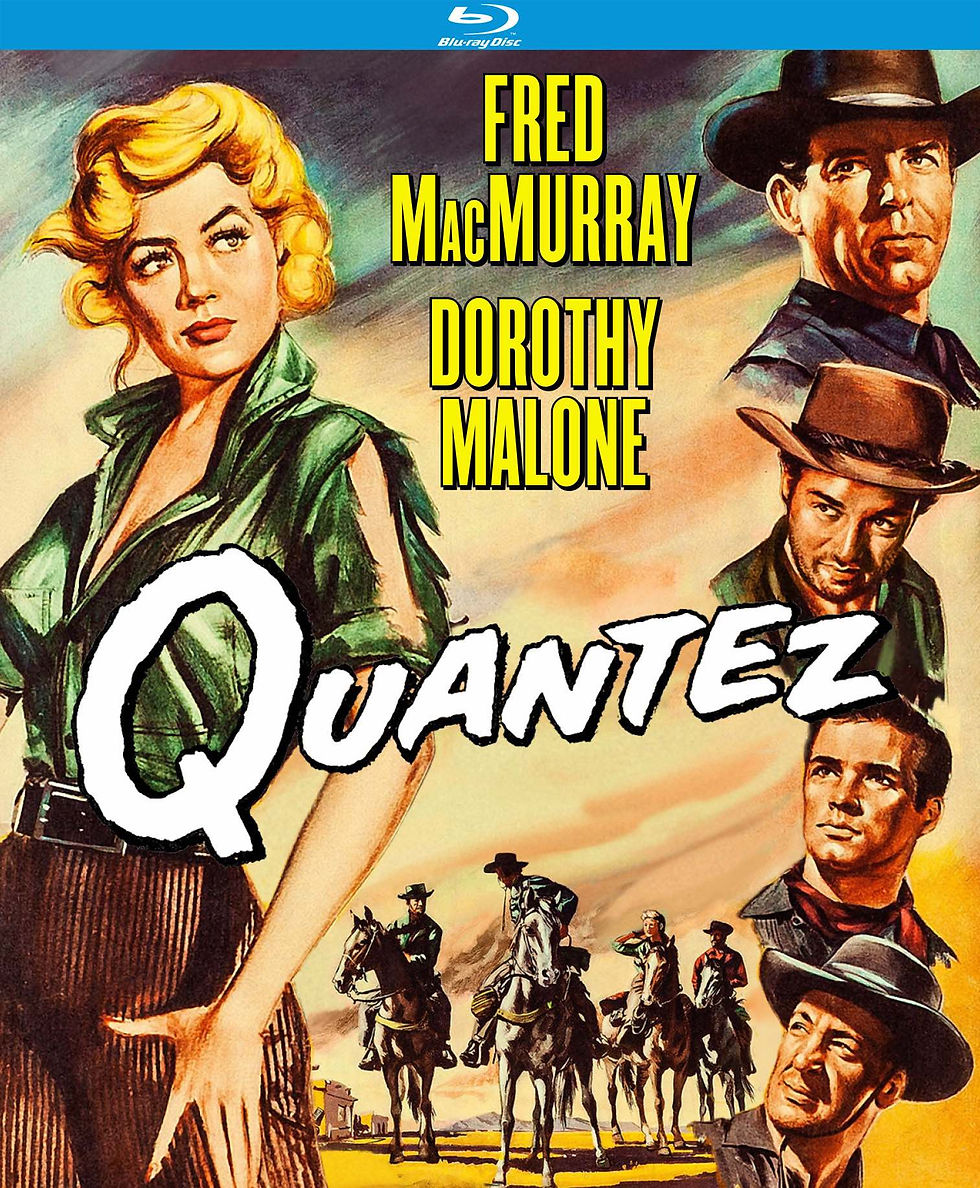

Quantez (1957)

Directed by Harry Keller

Produced by Gordon Kay

Screenplay by R. Wright Campbell

Story by Anne Edwards, R. Wright Campbell

Cinematography by Carl E. Guthrie

Edited by Fred MacDowell

Music by Herman Stein

Universal Pictures

(1:21) Kino Lorber Blu-ray

Quantez initially seems to embrace longstanding Western conventions only to turn them on their heads, leaving many 1957 audiences and critics confused, frustrated, or bored. Although filled with what some might consider formulaic elements, the picture feels grim and haunting, displaying characters drenched in mystery, suspicion, treachery, and desperation. Watching the film is like picking up a plot-driven paperback thriller, only to discover that its characters think they’re in a drama of Shakespearian proportions.

The film’s opening promises familiar components: the mysterious gunman, the woman with a past, the volatile brute of a leader, a greenhorn, and a man of mixed race and possibly mixed loyalties. We’ve seen these players many times before, and screenwriter R. Wright Campbell knows this. In fact you could watch the picture’s opening with the audio muted and still understand that this group of renegades, having just pulled a bank robbery, is attempting to lose the posse chasing them and find a viable hideout. This sequence could have served as the beginning of a hundred different Westerns, but once Campbell sets up audience expectations, he changes the rules. Instead of a plot-driven tale of the Old West, you’re watching a character study, a drama, and maybe even a film noir disguised as a Western.

Or perhaps it’s something else. Writer Timothy Evans may have summed up the film best when he states in his Letterboxd review, “Imagine The Thing (1982) without any actual monster and just a group of really well-defined character types trapped in an isolated location on the Mexican border slowly turning on one another.”

The outlaws find the town of Quantez strangely and recently abandoned. Once they settle inside an empty saloon, Quantez becomes a character study, somewhat similar to Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944), the film noir The Threat (1949), or a movie even closer in theme and setup, the woefully underseen noir Split Second (1953). Here we have five characters enclosed in a tight space, and something’s got to give. The audience soon begins to ask such questions as “What were these characters like before they came here?” and “How did they ever get together in the first place?” Perhaps the bigger question is “Who’s going to come out of this alive?”

Heller (John Larch) is the leader of this small band, a ruthless outlaw who killed a man unnecessarily during the robbery that occurs before the film starts. Heller is not only impulsive (shooting at the movements of rats inside the saloon, and later a dressmaker’s dummy), he’s unable to think beyond the immediate moment. Any foresight he has is expended only in determining how long the members of his gang will be useful to him. His reading and understanding of people is extremely limited.

He doesn’t know it, but Heller’s impulsive, violent nature is kept somewhat in check by Gentry (Fred MacMurray), the total opposite of Heller, an extremely observant gunman who always thinks several steps ahead. Gentry’s powers of observation have kept him alive for all these years, but being observant also requires energy and brain power. It’s clear from his first few moments onscreen that Gentry is tired and weary, and not just from the bank job. He’s hardened, burdened with the weight of the many deaths left in his wake. But unlike Heller, Gentry has retained an element of compassion. He knows, for instance, that in order to survive you must show kindness and care for the horses who get you where you need to go. After digging a shallow for the horses to stand in, he fills it with water and washes their legs. Gentry comments, “They see their way clear to carry us a long way and a hard time. They’re gonna need a lot of nursing and care.”

Gentry also shows compassion toward Chaney (Dorothy Malone), a former barroom singer who somehow found herself in the role of Heller’s woman. Chaney may be with Heller, but she’s looking for a way out. When Teach (John Gavin), the rookie of the group, encourages Chaney to leave Heller, Chaney responds, “I can’t leave Heller now, only be taken from him by somebody stronger.” Malone (almost always an underrated actress) conveys everything we need to know in her look of dejection and desperation, and we sense that she’s trapped in a cycle of abuse, probably not for the first time. Like Gentry, Chaney is a survivor, and she’s used her sexuality to survive. Her tough exterior holds true when challenged by men, yet crumbles when faced with the reality of the group’s desperate situation.

The outlier in the group is Gato (Sidney Chaplin, son of Charlie Chaplin), a white man raised by Indians whom Heller calls “Breed.” Gentry corrects Heller: “He’s no breed. He’s full-born white.” Gentry goes further, stating that Gato is “about the most valuable man around here.” Heller sees only through his own prejudices, but Gentry understands that Gato may be the only man the Apaches will listen to should the need arise. But until he knows the man’s intentions, Gato could be a savior or a killer.

I hope I’ve given you enough reason thus far to seek out Quantez. If you have not seen the film, please read no further until you’ve viewed it. If you have seen it, let’s continue this exploration:

SPOILERS

The relationship of Gentry and Heller is an interesting one. We sense that the two men have been adversaries for a long time, longer than the current robbery. You wonder how they ever got paired up. Perhaps Heller needed a strong gun, and Gentry was available. Heller doesn’t seem to know who Gentry really is, the legendary outlaw John Coventry, whom the peddler named Puritan (James Barton) sings about late in the film. Heller is clearly intimidated by the ballad, telling the minstrel to stop singing before the song is over. Maybe Heller has finally figured out that Gentry is Coventry, but Heller’s pride and impulsive nature won’t let him believe the truth. Yet Gentry practically gives Heller the opportunity to do something about it. After Heller says that instead of giving Teach a cut of the money, “I’ll give him his breath as his share.” Gentry responds, “What do you figure on giving me?”

We eventually learn what each character wants: Heller, to extend his power; Chaney, to be free from Heller; Teach, to be with Chaney; Gentry, to finally give up the life of a gunman.

But what about Gato?

We don’t know how long Gato has been marginalized by men like Heller, but the film’s opening gives us a subtle hint. After his horse collapses from exhaustion (and is eventually shot), Gato is forced to walk the rest of the way into Quantez. This may seem the only practical solution to his predicament, but no one offers to double up riding with him and probably not out of inconvenience. The indignity against him is clear.

When Gato meets the Apache chief Delgadito (Michael Ansara) under the cover of darkness, he articulates his loyalty to the Apache cause, caring nothing for his white companions. Gato suggests to Delgadito that he and his warriors kill the band of outlaws and take their money, or simply wait it out. After all, the robbers will soon kill themselves. The Apache leader refuses, stating that he just wants to clear the land of settlements, not start a war.

Ironically, Heller proposes the same action to Gentry: kill the others and split the loot. Gentry refuses. The difference is that we know Delgadito is going to attack the outlaws anyway, but not for their bank haul. Gentry isn’t about the money either. He has come to the conclusion that some things are more important than money, time being one of them, and while he may not have much time left to him, he does have a sense of dignity and finishing well.

Time is a concept that plays out differently for each character. Although we don’t know from the film’s opening who’s going to live and who’s going to die, we know not everyone will make it out of Quantez alive. Time will determine that. Gentry says as much to Teach: “There’s nothing to fight, nothing to test yourself against except time. You might as well fight that with us.”

The concept of time is also crucial for Puritan, whose life we suspect may come to an end at the hands of Heller at any moment, particularly once his ode to John Coventry is finished. Perhaps only as a way of extending his time and giving him opportunity to think, Puritan offers to paint Chaney’s portrait.

This scene sets up an amazing visual element that tells us something of Chaney’s now emerging character. Draped in a flaming red robe with Teach at her side, Chaney’s covering matches the freedom she feels in standing up to Heller, essentially declaring her independence. The color could also speak to her brazen past, one final reminder of where she came from, what she was.

The portrait itself is neither glamorized nor crude, rather representative of a peddler like Puritan: its subject is recognizable, but without detailed features that could solidify Chaney’s character. The rendering reflects her transition from who she was to who she’s going to be.

The scenes with Puritan are perhaps the movie’s finest. We’ve spent over an hour with these five (six counting Delgadito) characters, and the introduction of a new arrival invites questioning, not only of the new character, but also the existing ones. What does Puritan know? Why is he really here? Is he acting in the interests of someone besides himself, or is his presence simply bad luck in traveling?

Editor Fred MacDowell cuts the initial encounter between Heller and Puritan like a police interrogation scene in a film noir: quick cuts back and forth. (I also find it amusing that characters with the names Heller and Puritan are squaring off in conversation.) Soon afterward, Gentry has his own very different interrogation with Puritan outside the saloon. It is after this moment that all hell breaks loose for the film’s finale.

Earlier I mentioned that Quantez may indeed be a film noir masquerading as a Western. I mentioned the Heller/Puritan interrogation scene, but there are other noirish elements present in the film. Since the picture leans so heavily on dialogue, suspicion and interrogation become two of the script’s prime components. (Watch the way Gentry acts like a detective, pulling information out of Gato after his unexplained disappearances.) As stated before, the majority of the film confines its characters to small, claustrophobic spaces, usually in shadow. The eruption of violence is also a constant threat. And then there’s the theme of redemption, often a noir favorite.

Much credit should go to cinematographer Carl Guthrie, whose interior lighting is spectacular and can no doubt be best appreciated on this new Blu-ray from Kino Lorber. In many scenes inside the saloon, Guthrie gives us just enough light from outside to convey that these people have left all traces of life behind them. The shading and color of the characters in closeup reveals everything about them we need to know. Speaking of color, Eastman Color is just right for this film, not glitzy and glamorous like Technicolor, but grainy, less vibrant, the correct match for this ensemble of renegades.

Quantez is a film worth discovering or rediscovering, whether you are a fan of Westerns, film noir, or both.

Since the Kino Blu-ray contains a Toby Roan audio commentary which focuses largely on the lives and careers of those who made the film, I will leave much of that information for you to discover on the disc. Many thanks to Kino Lorber for releasing this fine film. (Blu-ray Region B releases of Quantez are also available from Koch Media in Germany and the Spanish label Llamentol.

I've been a fan of this movie for a very long time, and I never tire of pointing out its existence to those who have yet to discover it - I wrote a piece on it for my own blog earlier in the year as it happens.

I don't know that I would term it noir, although the lighting and certain thematic aspects do point that way. Overall, I think the redemptive core, the element which really drives its narrative along is too strong to allow me to view it as noir.

Colin McGuigan